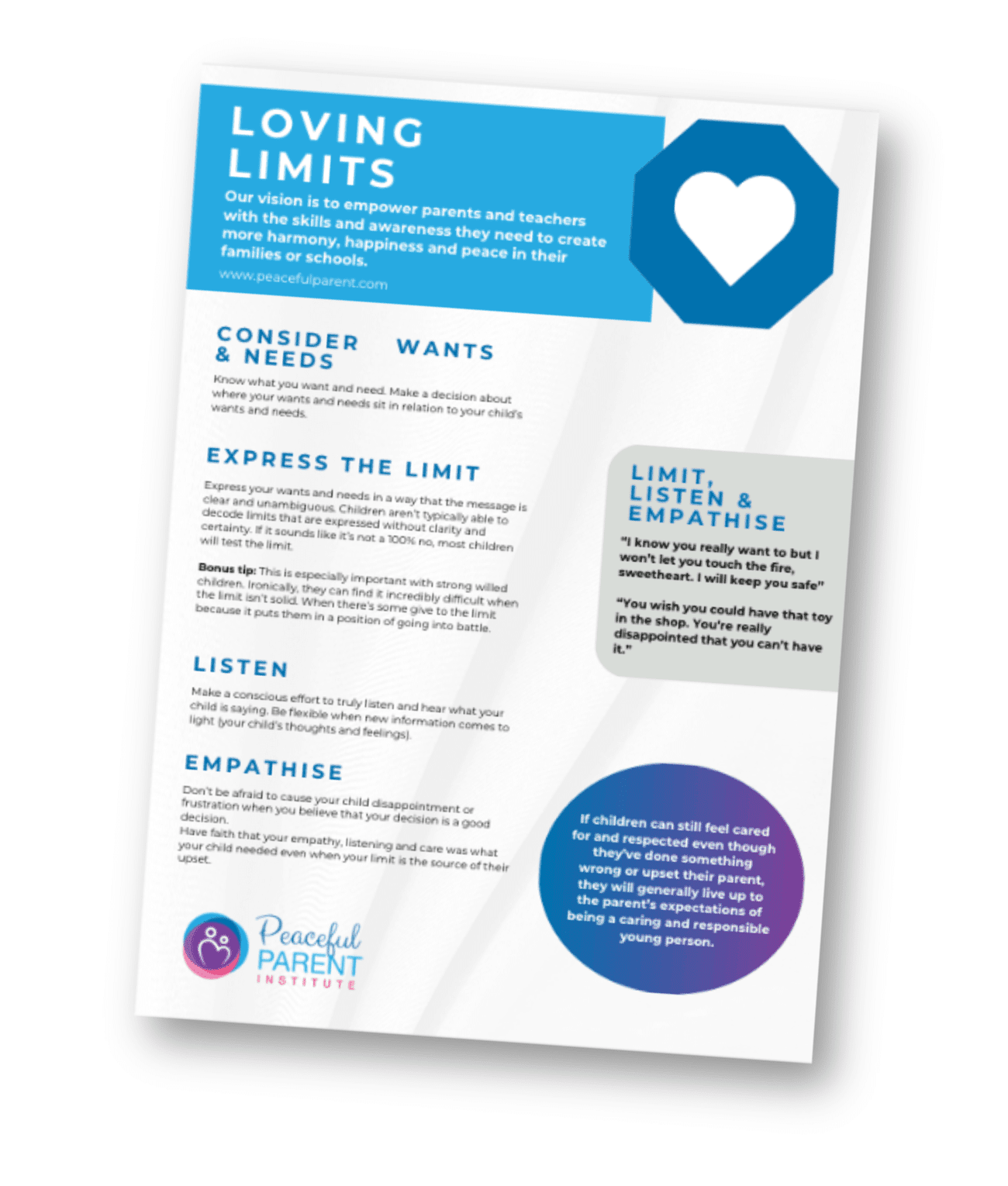

Download Genevieve’s free Loving Limits made easy PDF

A big question for most aspiring to be more gentle and patient parents is:

“If my child isn’t motivated by fear of punishment or anger, what’s WILL motivate them to do what I ask them to do. Or stop doing what I ask them to stop doing?”

Express limit, Listen, Empathise, Continue to hold the limit.

Most parents now realise why it’s important to move away from the traditional authoritarian parenting styles. We want our children to feel relaxed and secure, seen and heard. But we also need to maintain healthy boundaries in the family. Children are naturally egocentric and impulsive, we need to not make them wrong for being a child! Yet we need to intervene to maintain health, safety and positive relationships. This PDF will guide you through some helpful steps to: Consider wants and needs. Express the limit with absolute clarity. Actively listen and empathise and hold space for their feelings. While continuing to hold the limit.

Young children tend to cross other people’s boundaries quite a lot. They grab things that don’t belong to them, they can be over-enthusiastic in their expressions of affection towards the baby! They can lash out and hurt others (even the baby) either out of lack of awareness of others around them, or because they’re unable to contain huge amounts of frustration. They blurt out exactly what’s on their mind, which isn’t always seen to be cute! The whole world is their playground yet learning about all these boundaries and limits and what’s not allowed and not okay is a LOT to assimilate.

Young children tend to cross other people’s boundaries quite a lot. They grab things that don’t belong to them, they can be over-enthusiastic in their expressions of affection towards the baby! They can lash out and hurt others (even the baby) either out of lack of awareness of others around them, or because they’re unable to contain huge amounts of frustration. They blurt out exactly what’s on their mind, which isn’t always seen to be cute! The whole world is their playground yet learning about all these boundaries and limits and what’s not allowed and not okay is a LOT to assimilate.

Children tend to receive a lot of appeals to empathise with the person they’ve upset.

“Look how sad your brother is”,

“how would you like it if somebody grabbed your toy”,

“say sorry straight away”,

“now you’ve made me very very sad” displayed with an exaggeration of sadness,

“children won’t want to play with you when you do that”,

“that’s not how friends act”,

“that wasn’t a nice thing to do, was it”,

“now Granny’s not happy about what you did, she’s angry that you broke her vase, poor Granny, go and say sorry now”.

Yet such appeals tend to result in a child feeling more defensive than genuinely remorseful.

So how do we help our children develop empathy and impulse control? Children learn about empathy mostly through the direct experience of being empathised with and experiencing how it helps them feel better. This leads to the understanding that empathy helps *people* feel better. A child deserves and needs empathy not just when they’ve been wronged, but also when their desires and strong emotions lead them to act in ways that are anti-social. These are situations where a child is struggling and has much to learn and they need our patient guidance. They need empathy when they’ve done something they shouldn’t do, just as much as they need it when they injure themselves.

They can’t care about how they’ve upset another until they get that we care about THEIR upset.

Children rarely respond positively to an appeal to care for how another has been negatively affected by them if they themselves are not gaining the empathy and care that they need for their feelings *in this current experience*. “Can’t you see you upset your sister” is more likely to evoke more resentment towards little sister than empathy. This isn’t because they don’t care, but because they’re not gaining the help they need to work through the difficult emotions that the situation stirs up for them.

You might also like to read; Helping children when they hit, push and bite.

When feedback is delivered with care, it’s easier for the recipient to learn.

The message of care diffuses defences and ensures the parent’s positive influence. The image comes to mind of travelling in another country, there’s a lot of strict cultural rules about what’s okay and not okay and we only learn that we’ve been inappropriate when we get the feedback – how scary! We’d truly hope they had compassion for our lack of prior immersion into their culture and see our clumsiness as lack of awareness rather than lack of care or respect. And we need to be mindful that learning that it’s not okay to hurt others, for example, is just the beginning and a small part of what’s required for a child to better manage their intense impulses and emotions, be it frustration or excitement.

Should we make them say sorry?

With this question, it’s important to consider the outcome we want. Do we want them to simply say sorry (whether they feel it or not), or do we want them to reach the place of truly feeling remorse? Even adults usually take time to calm down enough to be able to look back at the emotionally charged situation with a wider perspective and be able to truly care about and consider the feelings of others. Not just intellectually but truly with empathy. When emotionally stirred up, children are operating from the emotional brain and are unable to ALSO access and operate from their prefrontal cortex, which governs empathy for others and problem-solving. They’re not yet developmentally there with this ability to feel emotionally aroused AND consider another’s feelings and have empathy for those feelings. They may say sorry but there may well be some shame. Their apology may be an attempt to end the very uncomfortable feeling of being in trouble as kids. Yet we don’t want to encourage them to express “I’m sorry” with the motivation of ending the discomfort of disapproval.

Maintaining a warm connection and care for the child while setting a limit preserves the child’s dignity and makes it MUCH easier to learn from the situation.

“I feel upset when you shout at me and slap me, I can’t let you do that (pause to breathe and re-center) – but I do really like and love you and I’m concerned about you feeling so grumpy and frustrated” – while touching her with care, affection and a show of empathy for the feelings that drove the behaviour.

Or “I don’t like when you push me to get my attention, (spoken with calm serious sincerity, but without any scorn or scowling, then pause to re-center) – but I do hear that you need my attention and I know it’s hard to wait”. (State what would work better) You can say “mum please answer me” and acknowledge “I know it’s frustrating when it’s hard to get my attention”.

Sharing your feelings with the use of non-blaming I Statements is helpful and often necessary feedback for a child when their actions are inappropriate, but it’s best if we contain our feelings long enough to first show them that we’re here to help and not condemn.

It’s SO much easier for a child to take on board the feedback or the limit once they’re reassured that we’re caring for their feelings in the situation, as well as reassurance that you know that they’re just learning.

When my kids were little I found myself saying to them quite a lot “it’s not a big thing, just a little thing” demonstrated with my hands and fingers to compare. I would share that to help them maintain their positive sense of self and put back in perspective whatever had just happened that drew my need to intervene or bring in a limit. I always wanted them to know that I care as much about their feelings in any situation, however big or small, as I do about the feelings of the other, or about the thing that’s been broken or the relative who felt insulted.

You might also like to read:

Here’s a list of articles which give more examples of what expressing limits and boundaries without punishment looks like, click here.

Expressing limits assertively but non-aggressively

Why children lash out and what to do

Child’s feelings and needs chart

Why we explode and how to prevent it

Little corrections and limits can feel like a BIG telling off to young children

Because children are so sensitive to and are so dependent on our love and care, they need us to be sensitive to their feelings and reassure them that all is still well. When the child has done something to upset another, it’s not our job to reprimand them, it’s a teachable moment that needs to be navigated sensitively. This can be a hard concept for many to get because nearly all of us grew up with the unchallenged beliefs that when a child does something wrong, then they need to be told in no uncertain terms how wrong they are and inherent in this is the agreement that they’ve at least temporarily lost the right to receive empathy and care for their feelings. And as a result, we live in a society where most adults lack the humility and skills to manage the emotions that conflicts trigger in them. Most adults will either become reactive and move into blaming and deflecting any responsibility. Most adults sweep conflicts under the carpet but the resentments build up and warm connections are compromised.

Let’s help our children learn from their many mistakes and experiences of crossing other people’s boundaries with loving guidance and kindness, not scrunched up frowning faces and pointing fingers and raised critical tones of voice. None of us like to be on the receiving end of that which feels so critical or scornful. None of us are motivated to open our minds and hearts to the input of those who are harshly critical of us.

You can communicate that the issue is serious and show your sincerity without becoming harsh.

And even when giving serious feedback or expressing limits and boundaries, there’s always a way to bring in messages of reassurance and care. Few things communicate care as much as a soft affectionate touch on the shoulder or arm, coming down to a child’s level and speaking with more kindness than scorn in your voice.

Children are greatly relieved to see our smile return, to be assured that we’re caring about their feelings as well and to feel the soft touch of our hand that conveys safety and warmth so powerfully. ~ Genevieve

Check out our Peaceful Parenting eCourses page to learn more the eCourses, videos, audios, parent child scripts, forums and resources that could give you the support you need to be the best parent that you can be!

i like this idea but my concern is what will happen when they get out in the world. And their friends or partners do not treat them this way. Will they be able to cope with the way others treat them?

I think being treated this way as a young child would actually teach them the skills to kindly and with empathy ask that others (friends, partners) treat them with respect. I think it would actually give them the skills to communicate well in mature relationships and also to know when to leave relationships in which they are not treated with the respect they are used to. Providing empathy and setting limits with them at this age will prepare them to do both of these things in their adult relationships instead of resorting to immature behaviour like giving the ‘silent treatment’ or yelling and name calling.

Uh? So how do you set a limit? Do you physically intervene to prevent them harming themselves or others? Do you physically intervene if they refuse your requests even after discussion? Or do you impose a consequence for that behaviour?

I like a lot of aspects of peaceful parenting but I hear very little on how to enforce a limit or boundary.

Cheers.

Hi Luke, Yes physically intervene to protect the one being harmed. If a parent asks a child to stop hurting and they don’t, continuing to raise one’s voice and demand may well be asking something of them that they simply can’t do because the child is so consumed by their rage and intense impulses and is still developing impulse control, so to physically get in between the two of them or take one of them onto your knee is necessary in protecting them. At the end of this article, is a link to other articles which give more information. This one better answers your questions: Helping children when they hit, push or bite: https://www.peacefulparent.com/680/ and The peaceful parenting approach to kids conflicts which also offers more strategies. https://www.peacefulparent.com/the-peaceful-parenting-approach-to-kids-conflicts/

And if you click articles on the blue menu you’ll see a drop down menu, click the section Loving limits and boundaries for a whole range of articles: https://www.peacefulparent.com/category/setting-limits-and-boundaries/page/2/

https://www.peacefulparent.com/from-biting-and-hitting-to-hugs-and-kisses-an-adoptive-mother-tells-her-story/

https://www.peacefulparent.com/3-y-o-ripping-wallpaper-off-walls-and-hitting-siblings/

This article you’ve read above gives more of an overview of the concept, it’s a very big and complex subject and I struggle to give parents all that they need in terms of the strategies even in a full day workshop because there can be so many different situations that a parent faces when their child is going through a phase of being aggressive, but I have quite a few articles that give different pieces of the information that’s needed. To put it all in one article isn’t possible.

Great post. Articles that have meaningful and insightful comments are more enjoyable, at least to me. It’s interesting to read what other people thought and how it relates to them, as their perspective could possibly help you in the future.

[…] limits assertively but non-aggressively Setting limits with love Active listening improves communication in the parent child relationship Empathy makes difficult […]

[…] though they are clearly the instigator! Counter-intuitive I know, yet without this element of maintaining connection while holding limits, all our talks, appeals and other strategies will likely just be experienced as further rejection […]

[…] of you showing genuine empathy for their feelings so they feel less alone with those feelings; holding the limit (assuming it’s a transition that needs to happen); and helping them maintain connection, […]

[…] eggshells. They avoid saying “No” at all costs in an attempt to avoid meltdowns. Yet limits help children develop their inner self-discipline. Just as importantly, the resulting big cries that limits tend to bring are often exactly what […]

[…] When choosing to co-sleep, babywear or feed their baby beyond a year, parents hear all these accusations. This, of course, is contrary to what’s known about the important role that meeting the child’s dependency needs plays in developing their emotional strength, security and resilience. The parent who chooses to homeschool is often accused of depriving their child of a “proper education” or healthy socialisation. The parent who chooses to not punish can feel judged to be permissive and too soft to hold boundaries or limits. […]

[…] mutual agreement. Although this often isn’t possible. Most people learned in childhood to fear limits and having boundaries asserted. When boundaries were asserted with shaming and punishing it sadly […]