Body autonomy, boundaries, and consent

Education at home and school combined is the best way of eradicating rape culture and creating a safer society for our boys and girls alike. Teaching children about consent, that they have the right to be kept safe and for their boundaries to be respected starts from the beginning of life.

There is generally a very positive growing awareness around the importance of a child’s autonomy over their own body. Parents (just like you reading this article!) are educating themselves on how best to talk with their child about their body. Parents are learning to not just avoid crass or disrespectful language that is demeaning but to help their children regain their dignity and innocence if they are exposed to confusing language or messages.

Moving away from shame

Part of moving away from a culture of shame is correctly naming body parts. Also speaking respectfully and matter-of-factly about the dos and don’ts of touching one’s own or another person’s private parts. We need to empower children to know they have the right to say no to any touch or treatment, sexual or otherwise, that makes them feel uncomfortable.

Many adults grew up hearing words like “dirty” or “disgusting” in response to, for instance, a child touching their genitals. Or even children asking questions about sexuality. This kind of language is very heavy and confusing for children. It brings the risk of children feeling ashamed of their body, ashamed for needing to ask questions or disclosing something uncomfortable they’ve experienced. Instead, parents need to respond calmly and maintain warm connection if their child is touching their genitals or asking questions about genitals or anything related to sexuality. It’s not about having one big talk, as much as generally staying calm and level and keeping the information age-appropriate in this area of education.

Abusers rely on the powerlessness and vulnerability of children and they rely on the child not telling. They generally work hard to assess this risk through observing the communication between a child and their parents or caregivers.

If you’re feeling a bit daunted, there are many great resources now available. They make it easier for parents to have these conversations with their children. Be proud of yourself for reading articles like this. I’ve mentioned some books and helpful websites at the end of this article.

There needs to be congruence between keeping safe information and the daily messages we give children

More and more parents are starting to see that they are giving their children messages about their bodies and consent every day through how they touch, treat and relate to them. Most parents are making a big effort to listen to their child’s likes and dislikes and giving more choices like “will I help you get dressed or do you want to dress yourself?”. As opposed to just briskly pulling that jumper down over their head without barely a warning or making a connection.

You might remember being handled like that when you were young. And might even have a sense of how that felt as you tune into such memories. Even though your caregiver would have simply been working hard to get things done, it might not have felt so good.

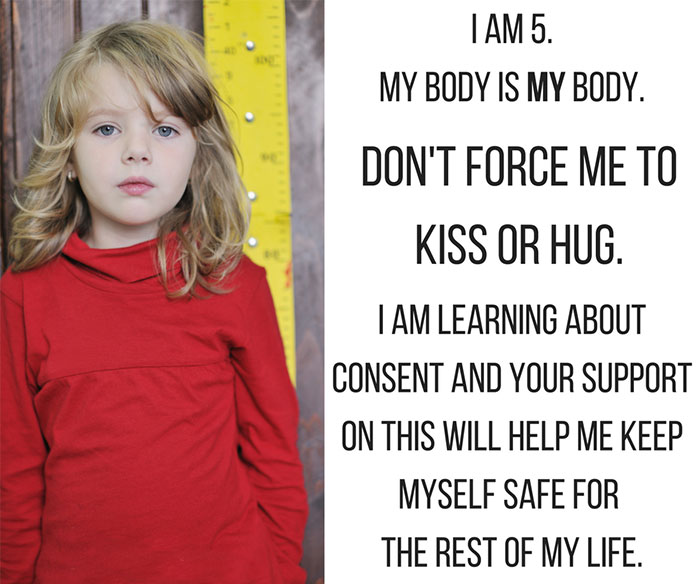

Children need to be given the clear message from the beginning of their life that their body is their body

That they have the right to give or not give consent to touch and affection. The baby makes it very clear if they don’t want to be held by Auntie May or Poppa Joe. But, they need their parent to care more about their feelings than Auntie May’s or Poppa Joe’s and respond appropriately.

Caregivers and children give and receive so many of these messages non-verbally in their day-to-day interactions. Babies, toddlers, school-age kids and teens give feedback about what they like and don’t like in many ways. Parents have to work hard to decode that communication. Patiently helping their child find the words to express their feelings.

This can be slow and sensitive work. But the child sees that their parent cares enough to slow down and work with them. And this helps to maintain healthy two-way communication. This communication allows the child to confide in their parent in the confidence that their concerns will be taken seriously.

“Come on, give me a big old hug!”

There’s a big difference between saying to the child “give me a hug!” as opposed to; “would you like a hug?”, or commanding “give grandad a big kiss.” We need to be very sensitive to the power difference (age, size, height, authority, dependence) and the extra weight this gives to that which we tell our children to do, and whether our communication is giving them the message that they have the right to say no.

Children generally like to please those they are bonded with and have a strong need for their caregiver’s approval, hence they need clear permission to protest. There can be a world of difference between a request and a demand. What feels like a demand to a child might seem like a request to an adult.

Preserving our child’s innocence and self-autonomy depends on ensuring they are free of feeling responsible for an adult’s emotional needs.

Children learn in so many ways if it’s acceptable to say “no” or not

This is learned through their parent’s reactions (or lack thereof) long before they gain the words. As their language develops, they need help to develop the vocabulary to maintain boundaries; “that doesn’t feel good”, “you’re too loud it’s scary”, “your hug is too tight I don’t like it”, “ouch that hurts”.

So many of the battles around dressing, eating, bathing, brushing teeth and car seats stem from the child tensing up in nervous anticipation. Persistent battles related to these daily activities are often symptomatic of the child being resistant because of stressful or distressing past experiences related to how gently or gruffly they’ve been touched. We need to every mindful of avoiding becoming forceful or gruff with our child if we’re to support them to develop a healthy relationship with their body, and healthy boundaries throughout childhood and adulthood.

Kids need to know that we have their back!

Showing your child that you take their feelings and their needs seriously and that you’re open to listening when they need help creates security. It’s important to avoid minimising their feelings with statements like; “oh you’ll be fine”, “no don’t worry”, “you’re making a big deal about nothing”, “you’re such a drama queen”, “there’s no blood, you’ll live”, “don’t be silly, you’ll have a great time”.

When we trivialise, deny or worse still mock a child for the feelings or worries they express, we train them to distrust and dismiss their uncomfortable feeling. Being in touch with uncomfortable feelings is often the child’s or teen’s best defence as it’s their warning bell that something doesn’t feel right.

If your child tells you that their teacher or sports coach was mean to them, don’t assume it’s an exaggeration or jump to the defence of the adult or accuse; “oh so what did you do that caused your teacher to get annoyed with you?” This message can result in a child believing that their parent will take the adult’s side and believe them over their child, it can sadly lead a child to believe that it really is their fault if an adult is unkind to them. Or worse still believing that they deserved to be treated disrespectfully.

Parents are often perplexed that their child didn’t disclose abuse, yet these messages (which can seem so unrelated to an adult) can sadly lead to a child who has been touched or otherwise treated inappropriately to not trust that they will gain the help and protection they need.

“Hey bro, it sounds like he wants you to stop”

Just as important as it is to be sensitive to our interactions with our children, parents need to advocate for their kids. Don’t be afraid to say “hey bro, it sounds like he wants you to stop” if a relative or friend is overstepping their boundary. Sadly most grooming happens through play.

It’s a well-known fact that abusers often groom children through humour and physical play. They gain the child’s trust and test where the boundaries lie, and quite often in the presence of parents and caregivers. Will the adult step in or do they even notice or seem uncomfortable? Will the child speak up? It’s a way of finding information about the relative safety of victimising a child.[/vc_column_text]

Daily care activities

It’s so important for the child’s healthy development to touch and treat them gently in the day-to-day activities of putting on their shoes, picking them up, wiping little faces or bottoms, restraining them in situations of danger or lifting them into their high-chair. Respectful, connected, kind and gentle care supports the child in developing a positive self-image. They feel safe, seen and cared for. They are taught through the embodied experience that they deserve gentle and kind treatment. Which in turn teaches them about the importance of being gentle towards others.

Kids generally need the communication around these daily activities to be so much slower, more relaxed, more connected, kinder, and more fun than a busy stressed under-pressure parent might realise. On the other hand, a child regularly feeling overpowered and treated gruffly can result in them learning to overpower their peers as children naturally re-enact what they experience. Or they become frozen in a powerless state when overpowered depending on the fight, flight or freeze response that gets activated. This freeze-stress response is often referred to as learned helplessness.

When children are rough-handled, touched, hit, pushed, pulled, pinched, poked, or tickled against their will

This gives a strong message about who has more rights over their body, and it’s not them. It’s a challenge to sensitise ourselves to our child’s delicate needs, it’s not always easy to slow down to the pace that makes it easier for the child and this shift in mindset can feel daunting for the parent whose parent’s insensitive touch and communication caused them to become desensitised to emotional needs.

Yet the more we practice this slower, kinder, more attuned and connected communication, the safer and more relaxed our child can feel in our presence. And subsequently, the more harmony and cooperation parent and child can mutually enjoy.

Sexual abuse is a scary topic for parents to contemplate

Many parents feel so powerless. Yet the good news is that there’s much that we can do to protect our children from the tragic experience of sexual abuse. Parents who think, talk, and address the topic of sexual abuse with other adults to educate themselves can go a long way in protecting their child from sexual abuse. Open lines of communication between caregiver and child can prevent the even very tragic experience of a child being sexually abused, then becoming frozen in silence, unable to confide. If the child does not feel safe to confide in the adult who cares for them, they will be unable to gain the help they need to prevent repeat experiences.

When a child is abused, the paedophile has attempted to contract them into secrecy, shame and silence. Yet when the abuse is exposed there is a great hope of the damaging impacts being remedied. All parents need to be aware of how crucial to recovery their response is. If a parent responds to the disclosure of abuse by ignoring, minimising or otherwise neglecting to fully engage to ensure they receive the emotional and therapeutic help they need to heal, they inadvertently add layers of secondary trauma and greatly compromise the hope of recovery.

A paedophile convicted of sexually abusing over a thousand boys shared many insights with the author Dr. Hammel-Zabin. Her book “Confessions With a Pedophile: In the Interest of Our Children, included these words:

“If the paedophile picks up the message that your children can go home and communicate, the paedophile will back off. Those kids are the safest kids in the world.”

#MeToo

I experienced sexual abuse during my childhood years and can retrospectively see the many contributing factors which made me so vulnerable and defenceless. During many long hard years of recovery, there was much to come to terms with. But dramatically the hardest reality to overcome was the awareness that over several years of abuse, just one truly sincere tuned-in conversation that gave me the permission and reassurance that I needed, to be honest, could have brought the abuse to an end.

Since the first disclosure at 17, just one conversation that expressed true remorse for the lack of that presence and protection and a genuine interest in retrospectively helping me gain the therapeutic interventions I needed, would have made it dramatically easier to heal the trauma.

Perhaps the easiest way to raise children who trust and value their feelings, their needs and their opinions and have a voice to express boundaries, is to show them that you take their feelings, their needs and their opinions seriously. The lack of this level of care is an experience that’s fairly consistent with those who experience ongoing abuse that they are powerless to end.

Recommended books to read with children

“My Body Belongs to Me” makes the topic of okay versus not okay touch very accessible and non-threatening for children.

It’s Not the Stork!: A Book About Girls, Boys, Babies, Bodies, Families and Friends does the same. It also covers the similarities and differences between a boy’s and a girl’s bodies. As well as a baby’s conception, growth in the womb, and birth, and an exploration of different configurations of families.

Check out our other recommended books to read with children.

Further Resources

Say “NO” to Bottom Games is a wonderful free eBook written by counsellor and therapist Anya Godwin. It some little stories divided into age categories.

New Zealand Police have some educational information for parents called Keeping Ourselves Safe. You can download it, and it is nicely divided into information for different age groups. Likewise, there’s some great information that you can access through CAPS.

Genevieve Simperingham is a Psychosynthesis Counsellor, a Parenting Instructor and coach, public speaker, human rights advocate, writer and the founder of The Peaceful Parent Institute. Check out her articles, Peaceful Parenting eCourses, forums and one-year Peaceful Parenting Instructor Training through this website or join over 90,000 followers on her Facebook page The Way of the Peaceful Parent.

Kia ora, can you please change the link for the ebook: https://homeandfamily.org.nz/ebook/ …. it was really hard to find the resource on the website. Its a good resource, thank you for sharing it.

Appreciate you letting us know Giarne. Have updated the link. 🙂

[…] Feel respected and valued – spoken to, looked at and touched respectfully. […]

[…] Emotional safety allows your child to be honest and not lie, to own and take responsibility for mistakes. Children need to feel emotionally safe in their family, which means that they can trust that their feelings and thoughts will be responded to with the sensitivity and respect that they deserve. This level of trust is what allows children to be honest about what they really feel and really need It's equally what allows them to be honest about their wrongdoings and what's needed for your child to not resort to lying as a defensive tactic. This level of emotional safety allows children to identify and be able to express that which they feel uncomfortable about, which is an important aspect of protecting children from different forms of abuse. […]