The following perspective change can help to transform conflicts into positive learning experiences. These two different approaches can relate to conflicts between any two or more individuals in a family, so although I’m mostly focusing on parent-child conflicts, but know that you can apply these concepts to conflicts in all relationships like teachers in the classroom, couples having marital conflicts, misunderstandings with friends or work colleagues. These approaches are especially important in helping the teenager maintain their stability and security in their relationships with family members.

The following perspective change can help to transform conflicts into positive learning experiences. These two different approaches can relate to conflicts between any two or more individuals in a family, so although I’m mostly focusing on parent-child conflicts, but know that you can apply these concepts to conflicts in all relationships like teachers in the classroom, couples having marital conflicts, misunderstandings with friends or work colleagues. These approaches are especially important in helping the teenager maintain their stability and security in their relationships with family members.

When using some of the connection and empathy-based communication skills shared below; differences and conflicts can become an opportunity to:

- deepen their understanding and trust of each other,

- practice sharing their feelings in a non-blaming way,

- practice active listening skills,

- practice mutual problem solving,

- and develop their practice of loving, compassionate nonviolent relating.

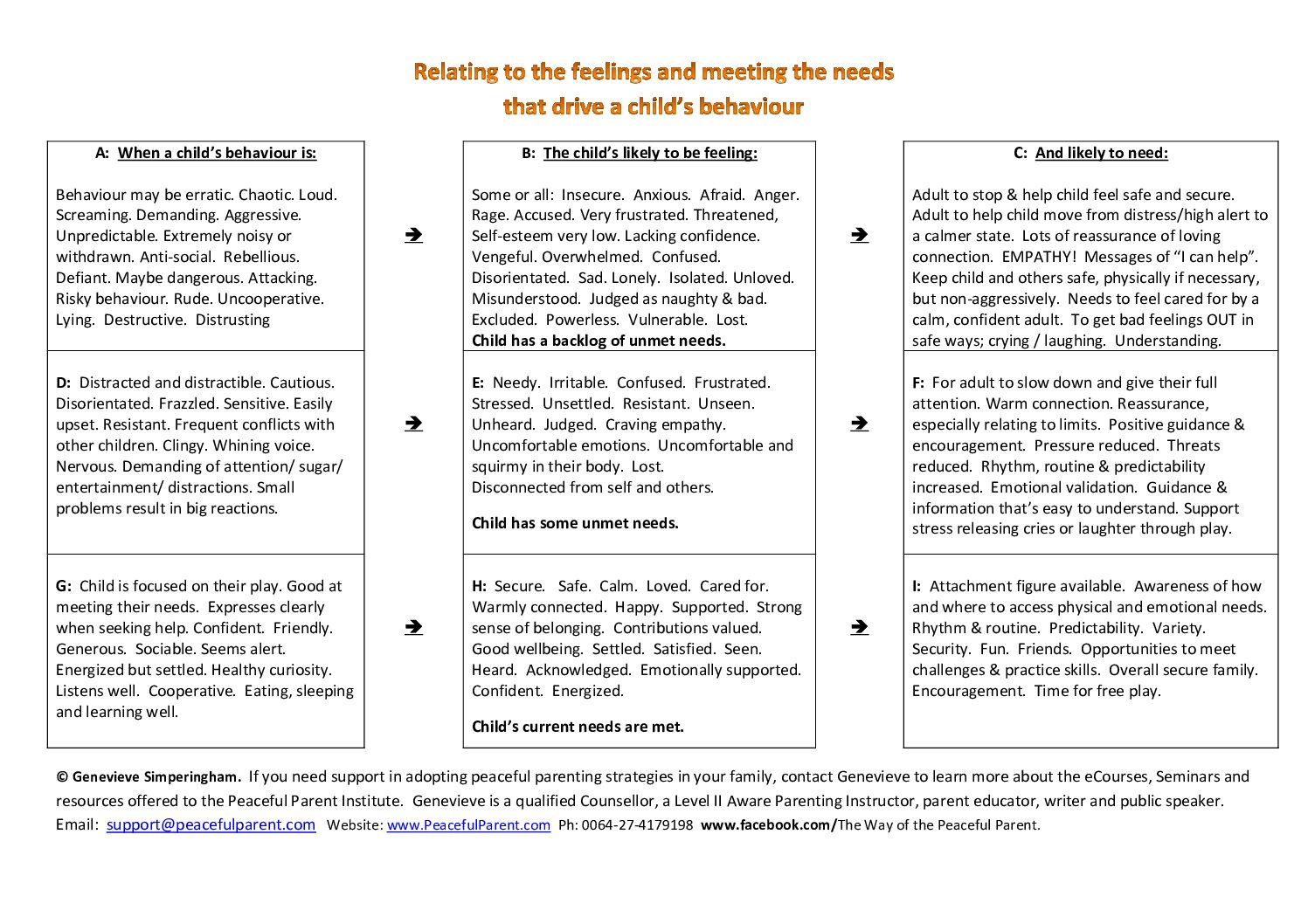

In the peaceful parenting approach, the parent aims to relate to the feelings and unmet needs of both their child and themselves and aims to creatively find a solution that meets as many of the needs as possible.

First, it’s important to understand that misbehaviour is seen to be symptomatic of some unmet needs or the child or the parent-child relationship is currently out of balance. There are needs to be identified and met in the trust that when a child’s needs are met, their behaviour tends to be much more balanced. Humans of all ages think and act more calmly, reasonably and creatively when their needs are met. Humans of all ages tend to become reactive and have much less capacity to act calmly, reasonably and creatively when feeling the stress of unmet needs.

Typical conflicts in the family are often sparked when a parent expresses a limit like “no you can’t have a biscuit right now” or a request “can you please pick up your toys?” Either the child reacts to the limit or the request, or the child doesn’t respond positively and then the parent reacts. Another typical cause of conflict relates to opposing wants and needs. The parent wants their child to come and eat or put on their p.j.’s but the child wants to continue with their play. The parent wants their child to go to bed, but their child wants another two stories. These kind of challenges are normal and happen in most families on most days.

In the old traditional model when conflict arises in the family; the objective is to figure out who is to blame and allot a punishment, often referred to as a “consequence” as the remedy for the wrongdoing or to otherwise coerce the child: When a conflict of wishes, wants, needs or opinions arises between parent and child, the parent’s urge is to blame, the child’s urge is to defend themselves, which results in the child blaming the parent or themselves and a power struggle ensuing. It’s as if the name of the game is to figure out who is right and who is wrong, which does nothing to foster true cooperation.

You might also like to read:

Expressing limits assertively but non-aggressively

Setting limits with love

Active listening improves communication in the parent child relationship

Empathy makes difficult feelings much less difficult

Aggressive acting out is a cry for healing

Family meetings

There’s an underlying belief that because the child has done or said something wrong or didn’t do what they were supposed to do, then;

- The child has to earn the adult’s trust again, “I’ll believe that you’re sorry when I see you fix it”

- The message is given in one way or another that the child who did “wrong” will only change, care or learn if they are told, in one way or another, how wrong they were.

- To make the child learn to behave more appropriately, there must be a consequence assigned by the adult as this is the only way the child will learn or care about the consequences of their actions (which generally feels very discouraging and disempowering for the child)

- The parent decides on an appropriate punishment (perhaps silence or withdrawal of something that’s valued, perhaps made to do extra chores),

- The child is given the message that the punishment is the consequence of the child’s actions or lack of action (refusal to do what they’re told) and they chose for this to happen by choosing to break a rule or not comply.

- The child is given the message that a consequence/punishment is being set because this is what ‘needs’ to happen in loving relationships, this is all part of the responsibility of a loving parent, this is what “love” looks like and this is how we learn to be a better person. The child is conditioned to expect painful consequences in response to their mistakes. And conditioned to believe that painful experiences in relationships are what they need and deserve.

- If the adult doesn’t impose a consequence, they let the child know that they are “lucky this time”, which effectively expresses a threat

- Children become scared of their parent’s disapproval. To avoid blame and rejection, they avoid taking responsibility and became very skilled at blaming others. Taking responsibility feels unsafe.

- In this culture, children will go to great lengths to hide their mistakes, to blame others, to attack as the best means of defence and to avoid taking on responsibility (like chores) that may result in making mistakes.

In the new model of relating to the feelings and unmet needs

When a conflict of wishes, wants, needs or opinions arises between parent and child, it is recognized that the parent or the child or both have feelings which need attention, and something to be worked through;

- When there’s a problem, we need to talk to better understand each other, we need to take turns listening to each other,

- Children repeatedly learn that misunderstandings need to be uncovered and resolved for solutions to be found or conflicts to be resolved,

- We trust our child’s inherent goodness, we trust that through honest, authentic, but sensitive, sharing of how each person feels, difficulties can be resolved. Even infants need and deserve to feel truly heard.

- Each person thus gains a greater feeling of being understood and respected as well as gaining a greater understanding of why the conflict arose and greater empathy for the other.

- We trust that both the parent and the child want to reach the place of repairing and solving the problem, but may need to feel heard and the child feel cared for first.

- The parent recognizes that when there’s an upset, connection must precede and accompany correction.

- The child learns through the natural consequence of seeing how their parent feels about what has happened “I felt very scared when I saw you climb up there, I was worried that you might hurt yourself”

- The parent’s ability to still show care, concern, love and support of their feelings in this challenging situation assures the child that they are still a good and lovable person even when conflict happens.

- Because the child trusts that their parent’s concern and guidance is coming from a place of care and because their feelings have been taken into consideration, the child can hear and consider their parent’s perspective and truly learn from the situation.

- In this family culture, children feel free to share and seek support from their parents when they make mistakes. They don’t have a need to hide their mistakes, to blame others or to attack family members because they are secure in the knowledge that all challenges will be worked through with consideration and care for everyone’s feelings and everyone’s unique perspective. Children are more willing to take on responsibilities like chores with the trust that they will be guided rather than criticized.

In summary: Children learn to react and treat others during conflicts in the same ways that their parent has reacted and treated them during conflicts at home. Children will respond to conflicts with their parent, with siblings, with their friends and even with themselves, in the same ways that they’ve seen modelled by their parent. When parents criticize, blame and shame, children do the same. When parents calmly talk through tricky issues while maintaining a positive connection with their child, children learn to do the same with their parent, their siblings and others.